The ArcticHubs project is moving to address what needs to be done to solve land, marine and resource conflict in the Arctic region. Whilst tackling considerations of the most appropriate ways to involve all the stakeholders, local populations, indigenous and other actors of the region, in the co-creation of effective tools for sustainable land and sea use planning.

In this interview with Vigdis Nygaard (senior researcher at NORCE and part of the ArcticHubs team), she introduces us to some recent research findings around geopolitical and global drivers impacting the Arctic scenario, a research of great interest for sustainable industry development of the region that should possibly sustain/inform private industries to fill key data gaps.

Could you first tell us something about yourself and your role within ArcticHubs?

I am a political scientist working at Norwegian Research Center – NORCE, one of the ArcticHubs project partner. NORCE is an interdisciplinary research institute with multiple locations across Norway, and I am based in Alta.

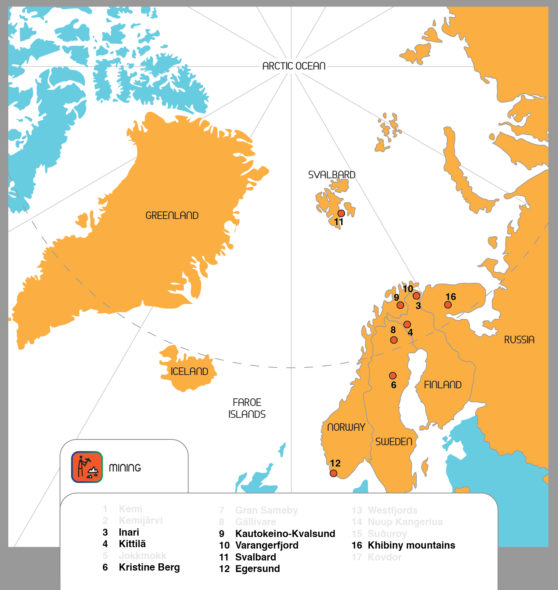

I have been working on industry development in the Arctic for several decades now. For the ArcticHubs project I am in charge of overseeing the research in the mining sector. I am helping to pull together all the data collected by researchers based in the 8 mining hubs of the project, and report their research results. Together with some researchers from NINA Institute, another ArcticHubs project partner, we are responsible for carrying out fieldwork in two Norwegian mining hubs: Svalbard and Kautokeino/Kvalsund.

I am also working closely with Leena Suopajärvi, who is coordinating a big chunk of research activities that focus on geopolitics and global drivers in the Arctic (the results of this have just been released over the Summer, you can read both reports here).

Working for the ArcticHubs project is improving my expertise as a researcher across different sectors and industries. It is helping to deepen my knowledge on how current global political situations affect the lives in local communities around the Arctic.

Regarding your recent investigation of the geopolitics of European Arctic, can you define what “geopolitics” means in your research?

Geopolitics is a concept usually used in political discussion, media and various academic disciplines. We have applied two mainstream geopolitical approaches: traditional and critical. The first refers to the politics of states with their sovereignty over territories and state-based international political bodies. Critical geopolitics, recognises that understanding the political governance of territory is also constructed through discourses, ideas, or values of different actors involved.

In the end, by geopolitics in our research we mean the political governance of the area and also the imaginaries of what and how the European Arctic is described and narrated in political and strategic papers.

In response to the ways that the Arctic is commonly imagined, we have recently released a short graphic explainer summarising the main misconceptions about the Arctic that the WP1 research findings have discoverd.

What research methods have you used for the analysis of the geopolitical and global drivers in the Arctic?

We have studied policy papers, national and industry specific strategies, alongside the conducting of interviews with industry specialists, NGOs, political representatives, and authorities. The interviews were analysed using thematic analysis. This means that we went through all the interviews and together with the researchers, specialists in the respective industry, we have extracted the dominating themes within each industry. Then we looked for different discourses, enabling us to grasp the variety of views.

Did any surprises emerge during this investigation?

Well, I was amazed by the considerable number of informants stressing the role of China in the Arctic. Many fears were raised about the possible dominance of China in acquiring access and ownership to Arctic resources, and how this can affect the supply side. I think we all learned during the last months of the war in Ukraine, that

unexpected global events can deeply affect the economic development of resource-based industries, as well as our personal economy.

What do the findings of your geopolitical research say about the Arctic region, its inhabitants and its future landscape?

The data is quite clear that all the industries we studied demonstrate a profound drive towards an almost unlimited growth in the Arctic region. The industries are aware of the challenges, such as vulnerable ecosystems, climate change, loss of natural habitat, or the need to take indigenous issues and interests into account. However, the research suggests those industries are more interested in mitigating and finding new technological solutions. Such actions can sometimes create further challenges, rather than securing their activities on a more sustainable level.

My fear is that the Arctic will be a battle ground for economic interests. Local people and local level politicians will also in the future meet a tremendous pressure from global industries investing in new resource development in the name of global demand and “green transition”.

What are the lessons learned from your research?

In terms of methods or our research approach – and in a way also in terms of findings – I have found it interesting to combine many forms of data searching on discourses and narratives around the Arctic. These have included official documents, national strategy papers, strategy papers from important international organisations, as well as in the direct interviews we conducted with Arctic stakeholders.

This approach has given us a holistic view on how the Arctic is defined in these documents, how it is approached, how it is understood.

How are the geopolitical research findings of interest to stakeholders in the Arctic?

I think it is important to highlight that this kind of research is key to plan strategically, where findings can be used by different stakeholders.

Take for example the different understandings of concepts used in the strategic papers, such as the term sustainability. The question to ask, is how is that term understood and used by different stakeholders to target their business goals? The European Union taxonomy will force big industrial actors to be more specific in their reporting on sustainability, and our research findings can enable more stakeholders to get the strategic knowledge needed for transparent business development in the Arctic.

Industry development in the Arctic requires a place and context specific approach. In the Arctic, standardised methods often taken from other countries, do not always fit and this is particularly true for Arctic industrial development.

National industry specific associations or organisations also have an important role in promoting their industry, both in political forums and guiding their members for better sustainability actions and reporting. These national industry specific organisations are therefore one of the main targets of our research reports and findings. They will benefit from this analysis as well, by more efficiently directing their businesses in alignment with EU policy and rules.

How is your research setting the ground for current and future ArcticHubs activities?

Our studies on geopolitics and global drivers have set the stage for the current discourses on significant industries present in the Arctic, on both a global and national level. Furthermore, this grounding research enables ArcticHubs researchers and partners to take this knowledge with them when conducting interviews and collecting additional data in the hubs. Besides this, all the organisations and institutions we have interviewed during this initial phase of work will form an appropriate forum for dissemination of subsequent results towards the end of the project.