Perched at the far northern tip of mainland Europe as the easternmost fjord in Norway, the Varangerfjord region is no stranger to thinking about adaptations and remaining resilient to complex and shifting circumstances.

It was a natural choice for the region to become one of the focal points for the ArcticHubs research team from project partner, NOFIMA, as they are able to draw upon extensive experiences of working with and alongside many users of this productive corner of the Arctic.

This brief article introduces research around the main livelihood opportunities that converge, interact, and take advantage of this 3,200km2 sweep of cold, clear polar waters. It highlights the significance of building long-lasting and interactive relationships with key stakeholders in the area. Contributing in turn towards an ongoing co-creative process, that allows the research to not simply hoover up data, but instead offer two-way collaborations that can help those concerned to move towards more durable solutions for the present and future utilisation of Varangerfjord.

The seminar in Bugøjnes this spring was one such engagement.

Over two days of lively discussion, voices and perspectives were gathered and are helping to contribute towards the shaping of a substantial coastal planning document for the region.

Located in a setting where terrestrial and maritime livelihood interests have long met, this was historically expressed through the Pomor trade – a barter trade between people in the area, trading grain products from Russia with fish from North Norway. Today, close to the significant geopolitical tri-point where the borders of Norway, Russia and Finland converge, Varangerfjord is a nexus of overlapping interests notably around aquaculture, commercial fishing, tourism and recreation.

To gain a more effective understanding as to how potentially conflicting interests may move to operate in more sustainable coexistence, it is important to hear local experiences and place the present situation in a longer-term context. A powerful narrative highlighting this can be found when looking back to the late 20th Century situation within the fishing communities of northern Norway. A time of crisis was reached in the 1980s following the collapse of cod stocks and subsequent loss of employment for many fisherman and ancillary services. The tipping point was reached for the port of Bugøjnes in 1989 with nearly half of the workforce unemployed and a population shrinking dramatically.

At that moment a group of local citizens made the decision to place a symbolic advertisement in a national paper stating that the town was up for sale and its residents would move anywhere that was willing to accept their migration! This dramatic gesture brought about rapid consequences.

Bugøjnes moved from being at the edge of the map and its crisis almost invisible in the wider public consciousness, to finding itself at the centre of political debate and a place where urgent actions occurred almost overnight.

Directly or indirectly the putting up for sale of the town triggered a search for more diverse and positive responses to its crisis.

One direction that was explored came in the unlikely transformation of an invasive marine species from villain to hero. The red king crab (Paralithodes camtschaticus), was first introduced into the Barents Sea by Russian scientists in the 1960s, far to the west of its natural habitat of Kamchatka and the Bering Sea. As it gradually migrated further west and ignored the bounds of territorial waters, the crabs turned up in the nets of alarmed Varangerfjord fishermen in greater and greater numbers.

The initial response to the invasion was to target a halt to the crab’s seabed march westwards and make the fishing of the species illegal. But with closer research concerning its adaptation to the environment in Varangerfjord and adjacent stretches of coast, along with a better understand of the commercial market for the species, the decision was eventually reached to create a quota system. This allowed local fishermen to take advantage of what soon became recognised as being a highly profitable catch. Fast-forward to 2022 and Varangerfjord is now at the center of Norwegian king crab production. The landing of live crabs represents a significant proportion of profits for many fishermen in the region. Whilst processing and shipping of king crabs to markets around the world, has created additional job opportunities onshore.

Observing the diverse set of attendees and interested groups present at the Bugøjnes seminar, and noting the themes of synergy and coexistence, it is clear that the fjord is important to more than a species of oversized crab.

Another prospect that emerged soon after the proposed sale of Bugøjnes, was the development of aquaculture in the form of fish farming initially for trout and then later salmon. Although fish cages had been present for some time in Varangerfjord

the gradual take-off of viable production in aquaculture aligned with the northward trend of warming water temperatures, a direct consequence of global climate change.

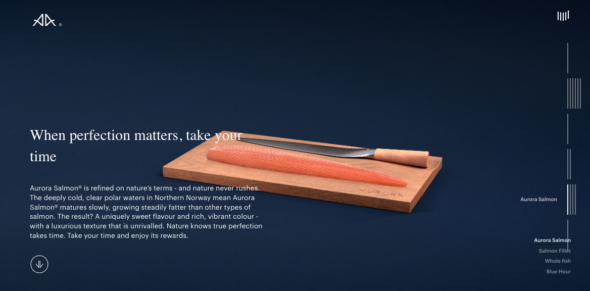

Currently, there are seven fish farming sites within the waters of Varangerfjord. Because of the still relatively cooler water, the fish here mature at a slower rate than in the sites further south along the Norwegian coast. This means that production rates are also lower. However, these aspects are being utilised as a positive marketing strategy with the slow growth of fish being linked to the popular ‘slow food’ theme where products are conveyed as being more natural, having better quality and are raised in more sustainable conditions.

Hence, even within this slower local situation all the farms are owned by Lerøy Aurora, a part of the Lerøy Seafood Group – Norway’s largest exporter of seafood, and one of the largest producers of Atlantic Salmon in the world.

An additional livelihood prospect that has also emerged around Varangerfjord, is tourism based upon nature and fishing. Again, the news and awareness of the situation in Bugøjnes inspired curiosity about the region and prompted a gradual growth in arrivals. More recently the polar nature tourism trends of stressed-out metropolitan residents wishing to see the aurora Northern Lights, fish on serene waters or relax observing migrating birds and whales, have led to a growth in job opportunities across the region.

During the seminar, in their own ways each of these livelihood sectors has looked out at the huge expanse of water, pointed to the current relatively limited activity in overall spatial terms and shared the thought that there should be sufficient room for expansion and further development in other corners of Varanagerfjord. For instance, it was cited that the total land use for aquaculture adds up to a total of 5 km2 (including the mooring area of the salmon cages) in a fjord area covering 3,200 km2.

Nonetheless it is recognised that the fjord is a common resource, with the difficulties experienced in the past have only been dealt with through coming together, listening, recognizing connections and seeking out collaborative responses. With this in mind, the ArcticHubs organised seminar represented another step in a sequential process of engagement and participation by a wide spread of interested stakeholder groups and individuals. The principal objective on this occasion being a contribution towards the Varangerfjord coastal plan. A collaborative venture that brings together the 4 municipalities around the fjord: South-Varanger, Nesseby, Vardø and Vadsø.

Raising a final, challenging point, the seminar noted that the creation of seemingly buoyant livelihood opportunities has not been enough to stem the flow of out migration to urban centres, or make up for the absence of facilities to attract families and young people, demonstrating that job creation alone is not a panacea for all the challenges facing a changing Arctic, and in turn leading to the crucial question

how to move from ‘employment’ to ‘settlement’?