Travellers are often warned of salmonella, and with good reason. It is one of the most common bacterial causes of food poisoning in the world and is still present in the European food chain– with the exception of Finland, Sweden and Norway. Only sporadic cases of salmonella have been detected in Finnish production animal farms in the 2010s. In the latest studies from 2000 to 2004, retail meat products of domestic origin were found to be completely salmonella-free, while in some EU member states the prevalence of salmonella in poultry flocks was found to be nearly 10% in 2015.

Most cases of salmonellosis are linked to consumption of contaminated foods such as eggs or inadequately heated chicken or meat. When preparing and eating meat dishes, infection can be avoided by ensuring hygiene at all stages of preparation and by consuming only thoroughly cooked (well done) meat. Raw eggs are problematic, as some types of salmonella may reside inside the egg, and not all foods containing eggs have been subjected to heat treatment that destroys the bacteria. A mayonnaise sandwich or pasta carbonara enjoyed during a trip may therefore result in an unpleasant intestinal inflammation.

In some cases, abdominal distress is not the only problem caused by salmonellosis, as individual patients may develop reactive arthritis as a sequela. Additionally, the latest research results indicate that some types of salmonella causing food poisoning appear to produce the same cytotoxin as the salmonella that causes typhoid fever. The toxin was found to damage the DNA of human cells, which may pose far more long-term health hazards than previously thought.

In the worst case scenario, salmonellosis may be lethal for patients who have low immunity at the time contracting the infection. According to WHO estimates, salmonella is the greatest cause of death among all foodborne pathogens resulting in roughly 59,000 deaths worldwide every year.

Salmonella is therefore anything but an insignificant pathogen internationally.

In addition to health hazards, big money is at stake. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has estimated that the total annual costs of salmonella amount to 3 billion euros in the EU. For the sake of comparison, the costs of antibiotic resistance, which has made many headlines recently, are currently only half of this in the EU. On the other hand, the trend in terms of resistance is much more worrying than that of salmonella.

Finland’s excellent salmonella situation is very exceptional internationally, and is not just due to our cool climate. We have succeeded in destroying salmonella almost completely in foodstuffs, through comprehensive control of the food chain and effective cooperation between producers and the authorities. An important contribution was also made by a great Finnish invention, a method known as competitive exclusion.

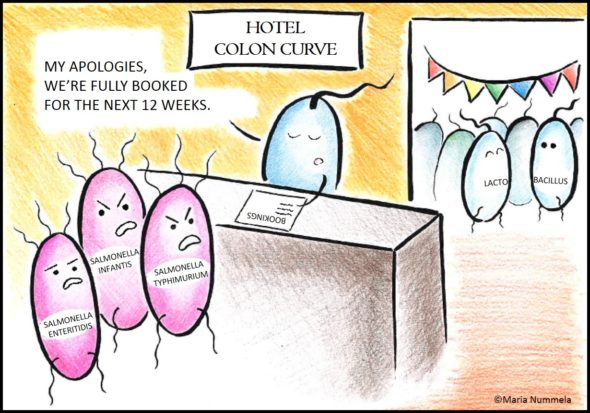

Competitive exclusion, the Nurmi Concept, was developed by Professor Esko Nurmi, Head of the National Veterinary Institute of Finland, the predecessor of the Finnish Food Safety Authority Evira, and his team at the beginning of the 1970s. In all its simplicity the method is in fact ingenious: newly hatched chickens are subjected to microbes isolated from the intestines of healthy broilers. In the intestinal tract of an exposed bird, these microbes take up all living space, preventing salmonella and several other harmful bacteria from spreading there later. The house has been occupied and there is no room for newcomers.

Competitive exclusion has been successfully used in Finnish poultry production since 1976. In addition, Finnish farms have long maintained extremely high standards of hygiene. Moreover, no fodder containing salmonella is used and every single bird carrying salmonella is eliminated from the production chain.

When Finland joined the European Union in 1995, our salmonellosis situation was already significantly better than in most member states. The aim is to prevent the re-migration of salmonella to Finland through the Salmonella Control Programme, involving the stricter control of fodder, food products and imported animals than in most other Member States. In addition, the European Commission has granted special guarantees to Finland: no meat or egg batches for which no evidence of freedom from salmonella is presented, may be imported into the country.

Fortunately, other European countries have improved their practices in recent years as well. Thanks to the EFSA-coordinated Salmonella Programme, the number of salmonellosis cases reported in humans in the EU has declined steadily since 2008. At that time, 134,580 cases of salmonellosis were confirmed per year, but this number had almost halved by 2015.

Regardless of the improved situation in other European countries, Finland, Sweden and Norway – and as regards eggs, also Denmark [1] – are still the only countries where the salmonella situation is so good that special guarantees have been granted.

A salmonella-free Finland is undoubtedly one of the greatest success stories in food control. Something of which the 100-year-old Finland can be truly proud.

[1] In February 2018, Denmark achieved special guarantees regarding broiler meat.

Maria Aarnio (nee Nummela)

Researcher

Finnish Food Authority

+358 40 489 3456

The original article was published on Evira’s website May15, 2017.

Photo in upper edge: Pixabay/rawpixel